- Home

- Mike Lupica

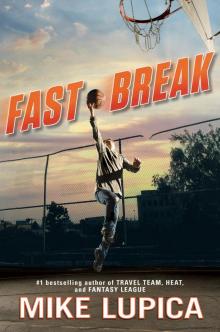

Fast Break

Fast Break Read online

ALSO BY #1 BESTSELLER MIKE LUPICA

Travel Team

Heat

Miracle on 49th Street

Summer Ball

The Big Field

Million-Dollar Throw

The Batboy

Hero

The Underdogs

True Legend

QB 1

Fantasy League

Philomel Books

A Penguin Random House Imprint

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Copyright © 2015 by Mike Lupica.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Philomel Books is a registered trademark of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lupica, Mike.

Fast break / Mike Lupica.

pages cm

Summary: Since his mother’s death, Jayson, twelve, has focused on basketball and surviving but he is found out and placed with an affluent foster family of a different race, and must learn to accept many changes, including facing his former teammates in a championship game.

[1. Foster home care—Fiction. 2. Basketball—Fiction. 3. Race relations—Fiction. 4. Homeless persons—Fiction. 5. Orphans—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.L97914Fas 2015

[Fic]—dc23

2015003511

ISBN 978-0-698-17557-0

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Basketball court & boy © 2015 by Adam Brown / Thinkstock

Cover design by Lindsey Andrews

Version_1

This book is for the great William Goldman.

Contents

Also by Mike Lupica

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

1

HIS NAME WAS JAYSON BARNES. But to his friends at school and on the court, he was known as Snap. His friend Tyrese Rice had given him the nickname one time, and it stuck.

“You’re like the basketball version of that Snapchat,” Ty had said. “One of those pictures you take with your phone and then it’s there, but only for a few seconds. Then it’s gone.” He snapped his fingers. “Gone.”

Jayson was all right with that. Sometimes he wanted to make himself disappear for real, from this part of Moreland, North Carolina, growing up this poor. Growing up mad. The guys he balled with at the Jefferson Houses, or the Jeff, as they called it, were always telling him how mad he played, the edge he had to him, the way he’d get into it with somebody on the other team the first time they gave him a shove or tried to get away with something.

It wasn’t like he didn’t have his reasons.

The Jefferson Houses were part of public housing on the east side of Moreland. There had been just one building at first, between the train tracks and the river, but now there were four: Jefferson, Washington, Adams, Lincoln—yet they were still known as the Jeff. And everybody on both sides of Moreland knew that the court there was where some of the best ball in town was played.

Jayson and his mom had lived at the Jeff until the landlord kicked them out for not paying the rent. They’d had no choice but to move to the Pines, a building even more run-down than the Jeff, practically right on top of the railroad tracks. When the trains would come barreling past, the walls of Jayson’s apartment would shake so bad it felt like an earthquake. He was just waiting for the day the entire building would collapse. That’s why he kept his basketball trophies in a drawer in his bedroom; he was sure that if he put them on top of his wobbly desk, they would fall and shatter one of these days.

Jayson had been embarrassed to move to the Pines at the time. Now he just wanted things back the way they were there.

These days, Jayson spent as much time as possible on the court at the Jeff. Most of the kids there were black, so Jayson would have stood out anyway, with his pale skin, long hair, and the old floppy socks that bunched up at the top of sneakers he’d grown out of from last year to this. But that wasn’t the real reason he stood out. It was the style and flash—and snap—he played with, the tricks he could do with the ball, and his all-around fakery.

Ty once told Jayson that he played blacker than any kid in the game, and faster.

“You ever notice,” Ty had been saying on the court just this afternoon, “how no one can ever stay in front of you? Like guarding something already happened.”

“Got to be fast to stay ahead,” Jayson said, looking at the high-rise buildings around them, the view always the same, wondering, like he did, if he’d have to wait until he finished high school to make his greatest move—getting out of the projects.

“Ahead of what?”

“You know what I mean. Ahead of everyone. Everything.”

Ty had nodded like he understood, but he didn’t, because even he didn’t know Jayson’s secret. Jayson loved Tyrese like a brother, but couldn’t trust him, because even at twelve Jayson had decided that the only person he could really trust was himself.

So he did what he always did when he felt himself wanting to drop his guard a little, and turned the talk to basketball. Just the night before, the Wizards had beaten LeBron and the Cavs, John Wall and Bradley Beal combining for 65 points. There had been long stretches in the game when you thought neither one of them would ever miss again.

“Ty,” Jayson said. “You think I got more John Wall in me, or Beal?”

“Wall,” said Tyrese. “A born point guard.” He faked a jump shot, his eyes following the imaginary ball as it swished through the net. “Me? I’m Beal, lighting it up from the outside.”

Jayson just smiled and nodded.

“That’ll be us someday,” Ty said. “At Carolina or Duke. You passing, me shooting. Cutting down the nets on the way to the Final Four.”

“No doubt,” Jayson said, not wanting to tell his best friend that when he was old enough to play college basketball, his plan was to get as far away from North Carolina as possible. Nothing against the state. It seemed like everybody here loved basketball as much as

he did.

He just needed to get away from his life, from going to bed hungry, from keeping his hair long because he couldn’t afford to go get it cut, from wearing sneakers that shamed him—because sneakers could, in basketball, when they were too old and too dirty and too small.

And his friends wondered why he played mad, why he was always up in somebody’s chest.

One time he’d even gotten into it with Shabazz Towson, the best center their age in town and one of his best friends. It had been the last game of the day at the Jeff, Jayson’s team up by a basket, needing one more to win by two. He beat his man, got into the lane, twisted his body at the last second to create space with Shabazz, tried to put up a teardrop shot.

Shabazz knocked both Jayson and the shot away.

When he tried to help Jayson up, Jayson slapped his hand away. Then he was right up on Shabazz.

“You got some cheap game in you.”

“Hey, man, we’re boys, remember?” Shabazz said before Tyrese pulled Jayson away.

“You’re on the other team,” Jayson replied. “On the court, you’re not my friend.”

Went right back to the rim on the next play, pulled the ball down, made a scoop shot to win the game. Then he glared at Shabazz and walked away, Shabazz knowing his friend well enough that it meant nothing, would be forgotten as soon as they left the court.

Jayson was smart enough about himself—smart enough, period—to know it was never just one thing. Being hungry and not being able to afford new kicks, that was only part of it. That was why he spent as much time on the basketball court as possible. Worked on his game as though it was all that mattered.

He knew there were things he could do just because he could, thinking that maybe God had given him a gift for playing ball because He had to give Jayson something.

He could dribble past a guy in a blink, put the ball behind his back or cross over with it. Could ball-fake you like he had the ball on a string. His friends told him he made the game look easy. But he knew how much of that came because of how hard he practiced.

He never got tired of practicing. It never bothered him being alone on the court, because even then, the game made him feel less alone.

So he’d picture the move he wanted to make, get it straight in his mind. Then he’d make it happen, sometimes feeling as if it were some kind of replay, because he’d already imagined it. It was the same way when he was getting ready to steal, the way he was now.

See yourself do it first, then be gone in a flash.

Like you disappeared.

But he knew making a steal required more than speed. You had to be smart, you had to pay attention, you had to pick your spot, pick the exact right moment to make your move.

Mostly what you had to do was watch their eyes, make sure your concentration was working for you the moment they lost theirs.

That’s when you had them.

It wasn’t just the element of surprise, Jayson knew, even though it was nice to have that going for you. No, as good as surprise was, acting cool was even better. The best kind of move was the one they didn’t expect. You had to let them think they were in control of the moment, when it was really you calling the play all along.

Jayson was almost there right now.

Waiting for him to turn his head, to take his eyes off Jayson just long enough.

Wait for it.

Jayson’s face the picture of calm, showing nothing.

Now.

The man behind the counter, Mr. Karlini, turned his head. Jayson, using those quick hands, put the loaf of bread under his sweatshirt. Then he walked calmly toward the door of the Broad Avenue Food Mart like he had all the time in the world, Mr. Karlini still talking to the old woman who’d come in at just the right moment to buy a lottery ticket.

Jayson still wasn’t taking any chances, didn’t want Mr. Karlini to look over and maybe spot the bulge in the front of his old Duke sweatshirt. So he angled his body just slightly away from him, trying not to be obvious about it.

He hadn’t been back to this store in a week, not since he stole the jar of peanut butter. Jayson tried not to hit the same store twice in the same week; he didn’t want guys like Mr. Karlini to get suspicious since he never actually bought anything.

Jayson kept walking at his normal pace, slowing down when he got near the magazine rack, stopping to look at the cover of HOOP.

“Something in particular you were looking for?” Mr. Karlini said, startling him a little. But Mr. Karlini was smiling. “Snap, isn’t that what your friends call you?”

“Nah, I was just hanging, Mr. Karlini, waiting for my friend. Guess he forgot me.”

“Well, you have a nice day.”

“You too.”

It bothered him a little when they were nice to him, and Mr. Karlini was maybe the nicest of all. But Jayson was out of bread and nearly out of peanut butter, and he was hungry. Every day he tried to fill up as much as he could on lunch in the cafeteria at Moreland East Middle. But then he’d get to playing ball and by the time he went home, his stomach felt so empty it was as if he’d never eaten at all.

The best nights were when Ty or Shabazz would invite him over for dinner, neither one of them ever saying anything about why they never got invited to Jayson’s. But that didn’t happen too often, especially on school nights.

The rest of the time, Jayson was on his own, something he had grown used to.

This was the way it had been since his mother had died and her last boyfriend, Richie, had up and left about a week later. None of his friends knew. Not about any of it. They just thought Jayson and his mom had moved to the Pines because they couldn’t afford the Jeff anymore, and that nobody had seen her lately because she was sick.

In truth, no one other than Jayson and Richie had even noticed his mom much when she was alive. Not for the last couple years of her life, at least. It was like she had already disappeared.

“I don’t think it was the drinking or the drugs that killed her,” Richie had told him. “I think she died from being sad.”

Jayson didn’t disagree, though he knew that the drinking and the drugs hadn’t helped. Anyway, the why of his mom’s death didn’t matter much in the end. The point was, his mom was gone. Then Richie was gone.

Only Jayson remained in the apartment at the Pines. And Jayson wasn’t about to let that change.

For now, Jayson was managing, stealing just enough to eat, trying not to think about what would happen now that there was no money left to pay the bills.

So far, nobody from Child Protective Services had come knocking at his door, but he knew it was only a matter of time before he got caught. A teacher was going to figure it out. Or Ty’s mother, or his coach at school, or somebody else. And then Jayson would either have to run faster than he ever had on a basketball court, or go into the foster care system.

The apartment may not have been much, not with his mother gone, but it was the only home he knew. Along with the basketball court at the Jeff.

He ran in that direction now, across Third Street, across Fourth, heading east on Broad, taking the bread out from under his blue sweatshirt, putting it in his right hand, pretending it was a basketball, pumping his hand up and down, air-dribbling it.

Jayson (Snap) Barnes was flying now. There one second. Gone the next.

2

THE BEST THING YOU COULD say about Richie Keegan was this: He wasn’t nearly as bad as some of the others his mom had brought around. But then, his mom had always thought that the next guy in her life was going to be the one who would provide her and Jayson the better life she said they both deserved.

Jayson knew his mom had loved him. And he had loved her. He knew how hard it was for her to raise him alone, before the drinking and the pills—and whatever else she was using when he wasn’t around to see—just seemed to swallow her up. When Jayson had

been old enough to ask about his father, all she’d told him was this:

“He was the first one who left.”

Jayson knew she had gone through all kinds of jobs when she was still able to work, before she just finally gave up, from hairdresser to waitress to housekeeper, until her real job seemed to become “going from one Richie to another.” Jayson knew she was always trying to get clean, going to her AA meetings, promising him that she was going to be a better person and a better mother, that she owed that to her little boy.

And he knew she always meant it. Even when she was making another mess in her life or trying to clean one up, as one man after another would leave her and make her sad, she was somehow still there every day when Jayson would come home from school or from playing ball. Jayson knew she didn’t love herself very much. But he knew she loved him and wanted to do better for him. She just didn’t know how.

Instead, she just seemed to get older and sicker. And so sad she essentially disappeared, never even leaving their run-down apartment.

It was late summer when Debbie Barnes died. Jayson had just started seventh grade.

With his mom gone, Jayson knew it wouldn’t be long before Richie left him too. At least Richie had scraped up enough money to bury his mother. An old friend of his worked at a small cemetery in Kirkville, about a half hour away. Richie threw the guy some money so they didn’t have to register the death, which Richie said would have had all kinds of people asking questions about what had happened to Debbie Barnes’s twelve-year-old boy.

They buried her one night in a cheap pine box. Jayson had asked Richie to put one of his trophies in with her. He remembered Richie saying some kind of prayer. All Jayson did was say goodbye. Then the two of them left Richie’s friend from the cemetery to do his job, Jayson knowing he was never coming back there.

Not long after came the night when Richie had shaken Jayson awake, his duffel bag packed and sitting at the end of Jayson’s bed, and told him he had to leave town.

“Like when?” Jayson said.

“Like now.”

“When are you coming back?”

Fool's Paradise

Fool's Paradise Batting Order

Batting Order Stone's Throw

Stone's Throw The Lacrosse Mix-Up

The Lacrosse Mix-Up The Hockey Rink Hunt

The Hockey Rink Hunt Payback

Payback Triple Threat

Triple Threat Defending Champ

Defending Champ The Turnover

The Turnover Robert B. Parker's Blood Feud

Robert B. Parker's Blood Feud Strike Zone

Strike Zone Hero

Hero Fantasy League

Fantasy League Robert B. Parker's Stone's Throw

Robert B. Parker's Stone's Throw The Big Field

The Big Field Jump

Jump Play Makers

Play Makers The Underdogs

The Underdogs Team Players

Team Players The Half-Court Hero

The Half-Court Hero QB 1

QB 1 Travel Team

Travel Team The Only Game

The Only Game True Legend

True Legend The Batboy

The Batboy Hot Hand

Hot Hand Million-Dollar Throw

Million-Dollar Throw Game Changers

Game Changers Miracle on 49th Street

Miracle on 49th Street Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill Fast Break

Fast Break The Football Fiasco

The Football Fiasco The Missing Baseball

The Missing Baseball No Slam Dunk

No Slam Dunk Heavy Hitters

Heavy Hitters Summer Ball

Summer Ball The Extra Yard

The Extra Yard Last Man Out

Last Man Out