- Home

- Mike Lupica

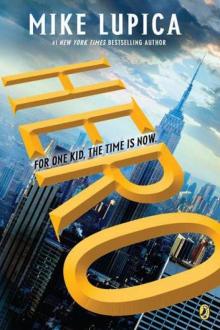

Hero Page 7

Hero Read online

Page 7

“If you don’t want to, I understand, I wouldn’t make you,” Zach said. “So let Alba take me out on the Jitney.” The Jitney was this cool bus people took from New York City out to the Hamptons. Zach and Kate had taken it a few times, loving life on it because it even featured wireless Internet service.

“Sorry, pal, but this conversation really is over,” Elizabeth Harriman said.

She could be the nicest, coolest, most understanding mom in the world. But when she dug in like this, Zach knew, you had a better chance of moving Madison Square Garden across Seventh Avenue.

“Let the boy do it,” Uncle John said. “Let him go there and be there and then be done with it. If you don’t, this will continue to be an itch he can’t scratch. And the discussion won’t end here; it will go on and on. And on.”

“John Marshall,” she said. “You know how much I respect your opinion. And how much I rely on your wisdom for all things relating to the welfare of this family. Just not this time.”

She gave him a look that Zach was pretty sure you wouldn’t have been able to dent with a hammer. Then she looked back at Zach and took an epic deep breath. “Maybe the next time we’re out on the island, whenever that is, maybe the two of us can take a drive out there one day. But for now, when the healing has barely begun, I don’t want you to do this. So you’re not doing this.”

Zach opened his mouth and closed it.

He thought, Healing? Was she kidding? What, she’d managed to patch up the hole in the universe his dad had fallen through and not mentioned that to anybody?

“I hear you,” he said to his mom.

He got up out of his chair, told Uncle John he’d see him and left them there with their tea and what he was sure was going to be a pretty lively conversation.

He hadn’t even made it up the first stair before the realization hit him.

He was making the trip out to Land’s End. On his own.

12

HE waited until Saturday morning, just because it would have been too complicated to pull off on a school day.

He and Kate were supposed to stop at the New York Public Library, the big branch, on 42nd Street, for a couple of books they needed on FDR. From there they were going to a one o’clock Knicks game, because Uncle John had scored them some prime tickets.

It would be the first Knicks game for him since his dad died.

Zach and Kate planned to take the Lexington Avenue subway down to the library, then just walk the rest of the way to the Garden. After the game they were going to stop at the ESPN Zone in Times Square, have a soda, maybe go to the third floor and play some of the games.

It was when they were about to walk down the steps at the 68th Street station, the Hunter College stop, that Zach told her. Having waited as long as he could.

“I need a favor,” he said. “A big one. Gi-gundo, in fact.”

“You got it,” Kate said.

She had her hair in a ponytail that came out through the opening of her favorite Knicks trucker cap. He knew she was wearing her David Lee No. 42 jersey under her parka.

“You might not want to say that when you know what the favor is.”

“Don’t have to know.”

“Okay, then I need you to cover for me,” he said. “I’m not going downtown with you. I’m going to take the Jitney out to Montauk.”

She pulled her cap down so low he could barely see her face now.

“But your mom said no,” Kate said.

“I know.”

“And you’re going anyway?”

“Yeah.”

She looked up and surprised him then. “I’m going with you.”

“You don’t want me to go any more than my mom does.”

“But if you’re going, and I can see you’re fixed on going or you wouldn’t have given me hardly any time to talk you out of this, then I’m not letting you go alone.”

“Thank you,” Zach said. “But no.”

“Why not?”

“Because the more I’ve thought about it, I’m almost glad Mom said no, ’cause this is something I need to do alone,” he said. “So just cover for me. Please, Katie. If I catch the next bus, I can get out there and get back by the time we’re due home.”

She shook her head. “We could go together and get back together and it’d be pretty much the same deal.”

Zach grinned. “I know you can out-debate me on stuff. Most stuff. Just don’t out-debate me today, okay?”

“What if you get back late? Then what do I tell your mom?”

“You’re Kate the Great,” he said. “You’ll think of something.”

She said, “You don’t have to do this even though you think you do. You can call it off right now and we can get on the train.”

“No,” he said. “I do have to do it. But I can’t without your help.”

“Just because I don’t agree with you doesn’t mean I’m not with you.” She pulled her cell out of the side pocket of her parka and held it up, like she was trying to sell it to him. “Four bars, fully charged,” she said. “I want calls or texts throughout the day. You don’t make a move out there without me knowing about it. Understood?”

He nodded. “I know better than to cross you,” he said. “It’s worse than crossing Jack Bauer.”

“Go get on the bus,” she said.

He did.

There was hardly any traffic going out on a Saturday morning and the Jitney was only half full, which made it seem even more quiet than usual. People were sleeping or reading or listening to their iPods. Zach had the longest trip, all the way to Montauk, about three hours out with no bad traffic.

It meant a six-hour round-trip. Plenty of time for him to get back to the city, meet up with Kate, be home for dinner the way they’d promised.

In the past he’d sometimes fallen asleep on the Jitney. But today he was too wired, wanting the driver to go faster, wanting to be out there right now. He looked out the window once they were on the Long Island Expressway, watched the exit signs go by way too slowly, Douglaston and Great Neck, Melville, Commack, Port Jefferson and Yaphank.

When the bus got off at Exit 70, Zach knew it was just about an hour from there to the last stop in Montauk. They made their way on Route 27 through all the towns Zach knew by heart, all the stops before Portugal. East Hampton finally gave way to Amagansett. He was close now, feeling it without having to look at any signs.

He had brought money with him. When he got into Montauk, he called the number of the taxi service he’d looked up the night before, knowing the crash site was too far for him to walk to from town.

When the driver showed up a few minutes later, Zach gave him the address.

The driver said, “There’s nothing out there but water and sky, kid.”

“There’s some other stuff,” Zach said.

“It’s your dollar. But I don’t feel right leaving a kid out in the middle of nowhere by himself.”

“Do you have a card with your number on it?” Zach said. “I’ll call you when I’m ready to come back to town.”

The driver handed him a card. “Your parents know where you are?”

“Oh, yeah,” Zach said. “And I’m from here.” As if that explained everything to the guy, like being a local was the same as having a signed permission slip.

As they drove away from town, Zach started to have the same strange feeling he’d had since he’d gotten up this morning, even before he was on the bus. The feeling that he was supposed to be doing this, supposed to be here.

Or maybe this was just one more way for Zach to test himself.

By the time the taxi pulled over to the side of the road, near the field where the plane had gone down, between the bay and the ocean, it really did look like Land’s End. Zach paid the man, watched the taxi turn around and head back toward town and felt as if he’d been dropped off at the end of the world.

He texted Kate.

Im here.

As he was crossing the narrow road, her reply came

back so quickly it was as if she were returning one of his shots in tennis.

B careful.

But it made him think of something his dad used to say to him all the time:

Be careful what you wish for.

He had wanted to come here. Wanted in some way to find his dad out here. Only now that he was here, he felt more alone than ever, small under the big sky you always saw when you got close to the ocean.

There wasn’t a house or building in sight.

He made his way through some tall grass and into the field, noticing some yellow police tape that had been left behind, like trash. It was like a sign that he was getting close to the place where the plane had fallen out of the sky, for reasons nobody had ever explained.

“Look to the sky,” his dad used to tell Zach when he was little and wondering what he would be when he grew up. “Look to the sky.” Well, the sky was empty now. The sky had betrayed him.

It took maybe a hundred yards more, and then he was there. In just about every news story Zach had read about the crash of Tom Harriman’s plane, they had talked about the “scorched” earth the first responders had found.

Finally he could see with his own eyes what they meant.

Around the hole in the ground where the nose of the plane must have hit, it looked as if someone had set fire to this field. And all around Zach could see other reminders of what the day must have been like: tire tracks in the mud that the police cars and emergency vehicles had left, more burnt and trampled grass.

Zach Harriman knew how much his dad loved flying, knew how much pride he took in it. He had been almost cocky about his ability to pilot a plane, talking about how he welcomed bad weather because that was “real flying.” When that pilot had landed the US Airways flight on the Hudson River, Tom Harriman and Zach had watched the highlights all day and all night and at one point his dad had said, “I’m jealous.”

“Jealous?” Zach had said.

“Yeah,” his dad had said. “That Sully got to make that landing instead of me.”

Zach walked a big circle around what Kate had said wasn’t a crash site anymore, but was. Not knowing what he was looking for, still wanting answers. Looking around and realizing there was no one around here to give him any. He noticed that even though it was early afternoon, the sky had grown dark, as if a storm might be on its way from the ocean.

The wind picked up, starting to howl.

Maybe his mom had been right. Maybe there was nothing out here worth seeing.

Zach had been angry since the crash, angry every day. But today he just felt sad, sad that he’d built this trip up so much in his mind, sad that he’d set himself up for this kind of letdown.

He walked away from the hole in the ground, toward the ocean, thinking he would soon come to the end of the field, some kind of fence or boundary. But he didn’t. He’d been able to hear the ocean when he’d first gotten out of the taxi, but not now. Now there was just the wind drowning out everything else.

The sky turned even darker.

Okay, I’m out of here, Zach thought, before this turns into the twister scene from The Wizard of Oz.

One more look at the hole in the ground, then he’d call the number on the back of the driver’s card. He hadn’t found anything, certainly not anything resembling a clue. But at least he’d come. At least he didn’t have to wonder anymore.

He walked back the way he’d come, arrived at the hole, knelt in the ruined grass, grabbed a fistful of dirt. For some reason he imagined his dad watching him now, from somewhere, from wherever heaven was, being proud of him for doing this.

Zach said good-bye to him.

He tossed the dirt away and started to get up, then stopped, because, as dark as it had grown, he saw a flash of light, reflecting off something.

Zach reached down and pushed the dirt away.

Felt the breath come out of him all at once.

Knowing what he was looking at the way he knew the password for his computer. Or the combination to his locker.

Or his dad’s face.

A Morgan silver dollar.

And not just any Morgan, Zach knew.

He knew of only two.

There was the one he was holding in the palm of his hand now and the one back home in the apartment, in his room, on the shelf above his bed. That’s where he kept it when he wasn’t trying to squeeze good luck out of it.

This was the one his dad carried with him wherever he went, to all the bad places. To this bad place.

Zach rubbed it against his jacket and then spit on his hand and cleaned it up a little more. His dad’s Morgan, no question. It was an 1879 and when he’d given one to Zach on his eighth birthday, he’d given this one to himself at the same time. Told Zach that day that from now on if he squeezed it hard enough, Tom Harriman would know, no matter where he was or what he was doing.

So Zach squeezed.

“I’ve been waiting for you,” a voice said.

13

THE old man wasn’t much taller than Zach. He had snow white hair, a lot of it, and a wispy white beard to go with it.

He was wearing faded jeans and one of those old leather bomber jackets that hung on him a bit, as if it were a size too large. A plain gray sweatshirt showed underneath it, and he had on a pair of old Reebok sneakers that looked older than he was.

He was smiling, maybe as a way of telling Zach not to be afraid. Like that was going to work.

“What do you think you’re doing, sneaking up on me like that?” Zach shouted.

“Didn’t think I was,” the old man said.

“Well, you’re wrong.”

“Calm down, Zach,” the old man said. “I’m sorry I scared you.”

“You didn’t scare me,” Zach said. “And how do you know my name?”

“Friend of the family,” the old man said.

He smiled again, put out his hand. Zach ignored it. “Then how come I don’t know you?”

“Simple. You weren’t ready yet.”

“Ready for what?”

“For you to know me the way I know you.”

It had taken all of a minute for Zach to feel as if he were walking in circles, even standing still.

“You said you’d been waiting for me?” Zach said.

“So I did. And so I have.”

“You haven’t told me your name.”

“Call me Mr. Herbert.”

“Okay, Mr. Herbert. You live around here?”

The old man shook his head. “I was just out here observing, I guess you could say.”

“How come I didn’t see you before this?”

“Because I didn’t want to, Zacman.”

It startled him. Only his dad had ever called him Zacman. Ever. It had started as a joke, because when he was little, Zach was always eating on the run.

“I don’t need Pacman,” his dad had said to him one time. “I’ve got my very own Zacman.”

It had stuck. For his dad, anyway. No one else had ever called him that.

“Don’t call me that,” Zach said now.

“I’m sorry. I know that was your dad’s nickname for you,” the old man said. “Like I told you, kid. I’m a friend of the family.”

“Who’s been waiting for me out here.”

“Correct.”

He thought of the way the taxi driver had described this place. “The middle of nowhere.”

For some reason, Zach flashed to all the times he’d been told not to talk to strangers, the way all kids are told that from the time they’re old enough to walk out of their parents’ sight. Now here he was with this perfect stranger, this old man who seemed to know way too much about him.

And who talked in riddles.

“You keep saying you’re a friend of the family,” Zach said. “But I don’t recall my dad ever mentioning a friend of his named Mr. Herbert.”

“No reason for him to. There was a lot your dad never told you about himself. Am I right, Zacman?”

“I told

you: stop calling me Zacman.”

“As you wish.” Mr. Herbert smiled. “And you can put the coin away; I promise I won’t steal it.”

Zach looked down, opened his hand, as if to make sure the Morgan was still there. He said, “How did you know . . . ?”

“Because I know about you,” Mr. Herbert said. “It’s what I’m trying to tell you. I know about your father’s death and I know about your life.” His eyes darted all around as he nodded. “A life that we both know is changing faster than the weather.”

Zach stared at him. This old man who not only knew what was in his hand, but what was in him. He thought about turning and running, getting away from him right now, but knew he wouldn’t.

Knew that somehow Mr. Herbert was the reason why he was here.

“There are things you need to know about your father,” Mr. Herbert said.

“Like what?”

“Like how much of his life was a lie,” the old man said.

A blast of wind nearly knocked both of them over as a huge thunderclap boomed from out east, over the water.

“My father didn’t lie,” Zach said. “Ever.”

“That may be a matter of opinion.”

“What do you want from me, Mr. Herbert?”

“Let’s start by taking a walk.”

He started to put a hand on Zach’s shoulder. Zach leaned away from it, like a boxer pulling back from a punch. The old man shrugged and made a gesture that said, follow me. Zach did, a few steps behind.

Maybe fifty yards from where the plane had hit, on the bay end of the field, was a stone wall he hadn’t even noticed. The old man sat down when he came to it, patted a spot next to him.

“Just a second,” Zach said, and pulled out his cell, checking the time on it. One-twenty. He couldn’t chase Mr. Herbert around this conversation forever, like chasing him around a video game. Or through a maze. The Jitney was scheduled to go back to Manhattan at two o’clock.

He thought about texting Kate. . . .

“Call her if you want,” Mr. Herbert said. “Won’t bother me. I was sort of hoping you’d bring her along.”

Fool's Paradise

Fool's Paradise Batting Order

Batting Order Stone's Throw

Stone's Throw The Lacrosse Mix-Up

The Lacrosse Mix-Up The Hockey Rink Hunt

The Hockey Rink Hunt Payback

Payback Triple Threat

Triple Threat Defending Champ

Defending Champ The Turnover

The Turnover Robert B. Parker's Blood Feud

Robert B. Parker's Blood Feud Strike Zone

Strike Zone Hero

Hero Fantasy League

Fantasy League Robert B. Parker's Stone's Throw

Robert B. Parker's Stone's Throw The Big Field

The Big Field Jump

Jump Play Makers

Play Makers The Underdogs

The Underdogs Team Players

Team Players The Half-Court Hero

The Half-Court Hero QB 1

QB 1 Travel Team

Travel Team The Only Game

The Only Game True Legend

True Legend The Batboy

The Batboy Hot Hand

Hot Hand Million-Dollar Throw

Million-Dollar Throw Game Changers

Game Changers Miracle on 49th Street

Miracle on 49th Street Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill Fast Break

Fast Break The Football Fiasco

The Football Fiasco The Missing Baseball

The Missing Baseball No Slam Dunk

No Slam Dunk Heavy Hitters

Heavy Hitters Summer Ball

Summer Ball The Extra Yard

The Extra Yard Last Man Out

Last Man Out